Adrienne Martini & Russell Letson Review The Raven Tower by Ann Leckie

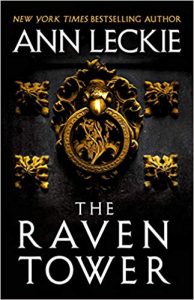

The Raven Tower, Ann Leckie (Orbit 978-0-316-38869-6, $26.00, 432pp, hc) February 2019.

The Raven Tower, Ann Leckie (Orbit 978-0-316-38869-6, $26.00, 432pp, hc) February 2019.

You likely know Ann Leckie from her multi-award winning books set in the Ancillary Justice universe. These books took a sub-genre we know well – space opera – and told it slant. Yes, the tales spanned galaxies and generations, but her vision filtered these hoary old tropes into something fresh by focusing on gender and identity, while still telling a propulsive story that doesn’t forget that fiction should always be engaging even when it is thoughtful. With The Raven Tower, Leckie plays in the world of fantasy, rather than science fiction, and proves that she is a great writer no matter the genre.

The outline of the plot mirrors Hamlet: a disaffected heir to the throne returns (from a war, not college, in this case) to his home kingdom to ascend to the throne. Instead, he discovers his uncle has already made himself king (or, in this case, the Raven’s Lease). Mawat, Leckie’s Hamlet analog, loses his grip and unleashes his great temper. There is a ghost, sort of. There is an unfortunate stabbing. There is an Ophelia-esque childhood friend. And, like Hamlet, the stage is littered with bodies by the end.

What Leckie has added is what makes this story fresh. Our narrator is a god, whose motivations are suspect, at best. Our Mawat is left to his own devices to navigate his madness; instead, he has Eolo, the Wooster to his Jeeves. The god/narrator also tells Eolo’s story, but in the second person, which works once you get used to it. This story builds in surprising ways, both in terms of plot and how it is told.

Leckie’s first Ancillary book made a well-trod part of the science fiction world feel like it had new ways to say new things. With The Raven Tower, she proves the same for the gods, mortals, and magic sub-section of fantasy.

–Adrienne Martini

Nobody is going to mistake Ann Leckie’s The Raven Tower for off-the-shelf heroic-fantasy yard goods, despite its being set in a medieval-level world, populated with familiar character types (warriors, courtiers, priests and priestesses, supernatural beings), and deploying a plot that turns on both magical and muscular powers. All these familiar components, along with others unlisted, are given a quarter- or half-twist and set in unexpected relationships to each other.

For starters, the narrator is a god. Not only that, but a god who direct-addresses the whole story to one of the characters – the opening line begins, “I first saw you when you rode out of the forest” – which means that much of the novel is cast in second person, a choice guaranteed to set some readers’ teeth on edge. (It did mine, until I figured out what was up, storytelling-wise.)

There are actually two gradually converging narrative threads: one that would conventionally be the main (human-centric) plot, as told to one of its protagonists, and one that is the narrator’s own story, reaching back millions of years to its earliest memories of submersion in water inhabited by “scuttling sea scorpions and trilobites, coil-shelled ammonites.” The god’s physical home or form is a large rock, which endures through the geologic ages, until it is noticed by the various groups of humans who become its devotees. And very gradually we discover how it came to witness the events of the present action.

The human-centric story is a familiar one: a young nobleman, Mawat, comes home to the city of Vastai to find that his father, a kind of priest-king, has vanished and been replaced not by the presumptive heir (himself) but by Mawat’s uncle, who has popped in between the election and his hopes. The story’s focus, however – the “you” addressed throughout – is not Mawat, but his companion and aide-de-camp Eolo, a backwoods warrior who has risen from humble beginnings on the basis of his intelligence, skills, and loyalty. So a second twist: the human plot is a version of Hamlet, observed over Horatio’s shoulder by a god.

Why the god chooses to focus on Eolo rather than Mawat is one of a series of puzzles and slow reveals, many of which are connected. For example, the nature of Vastai’s government is intertwined with the nature of godhood and the relationship between gods and humans. Vastai’s head of state is called the Lease, who communicates with the city’s god, called the Raven, via its Instrument, an actual, mortal raven housed in the tower of the title. When the Instrument dies, the Lease must give up his own life as a part of a system of sacrifice and mutual human-divine benefit. Vastai is not the only city or people or territory with protective or beneficial arrangements with gods. The bordering and shielding forest has its own supernatural guardian, and Vastai’s rivals on the far side of the forest make a deal with a different deity as part of their continuing conflict with the city. In fact, human diplomacy and conflict would seem to always involve alliances with one or more gods.

As powerful as gods are, they are not endlessly so, and the god in the stone seems to be a modest sort, uninterested in projecting divine power and influence beyond its local territory and clientele. We see this in the narrator’s look back at its own long existence, which includes explanatory chunks addressing various facts of godly life, often presented as received stories, because

Stories can be risky for someone like me. What I say must be true, or it will be made true, and if it cannot be made true – if I don’t have the power, or if what I have said is an impossibility – then I will pay the price.

So the god’s statements and explanations are often cast in the subjunctive or start with “Here is a story I have heard.” The price for over-promising or exaggerating is a dangerous or even fatal power drain, as the universe seeks to make the divine utterance true at the god’s expense, so prudent gods keep their promises safely in proportion to the payments their petitioners can afford – prayers, small offerings, or sacrifices – that sustain the god’s power, and more ambitious gods require bigger offerings.

The divine back-story reveals an ecology and economy and even a politics of gods – there have been wars among these beings, and there remain rivalries and competitions for as well as among worshipers. The god business unfolds in all its complexity: prayer, propitiation, prophecy, divination, sacrifice, oath, obligation, talisman, fetish, miracle, mana. Through the ages, the god in the stone – called Strength and Patience by one worshiper – does small favors but mostly just watches, and one wonders why and how it came to observe the dark business of the Vastai succession – why it should care about what’s going on in the Raven Tower.

I suspect that as much of the fun of reading The Raven Tower will come from assembling an understanding of its supernatural environment as from following its human plot’s mashup of Hamlet and sword-and-sorcery adventure. This is a thoughtful reimagining of a genre, a re-examination featuring the same kinds of variations, inversions, and overturned expectations that Leckie visited on the military SF/space opera formula in the Ancillary books. Everything here will repay close attention, and much will draw a smile of recognition or of plain old pleasure at smart writing and surprising reinvention.

–Russell Letson

Adrienne Martini has been reading or writing about science fiction for decades and has had two non-fiction, non-genre books published by Simon and Schuster. She lives in Upstate New York with one husband, two kids, and one corgi. She also runs a lot.

Russell Letson, Contributing Editor, is a not-quite-retired freelance writer living in St. Cloud, Minnesota. He has been loitering around the SF world since childhood and been writing about it since his long-ago grad school days. In between, he published a good bit of business-technology and music journalism. He is still working on a book about Hawaiian slack key guitar.

This review and more like it in the February 2019 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.